Choosing the Right Dependency Between Project Activities

The schedule logic for a project is the collection of dependencies you create between activities. The goal of this schedule logic is to provide a realistic model of when project activities should occur. Want to up your scheduling game? This article explains when to use each dependency type to link activities.

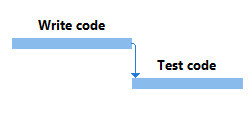

Finish-to-start is the one you’ll use most often. A finish-to-start dependency tells you that when one activity (called the predecessor) finishes, the next activity (the successor) can start. For example, you have to finish writing some code before you can test it. If you don’t work in software, maybe this example will resonate: when your older child teases the younger one, the younger one starts crying.

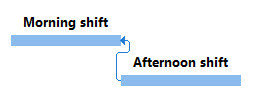

On the other hand, the start-to-finish dependency type is rare (which is a gift because it’s also confusing). This dependency means that the start of one activity determines when another one finishes. It’s confusing because the predecessor occurs later than the successor, as shown in the figure, and most people think of predecessors occurring before successors. (Remember, with dependencies, the predecessor is the activity that controls the timing of the successor, not when it occurs time-wise.) For example, consider a sales clerk who works a shift in a retail store. To keep the store open for customers, the clerk for the next shift has to show up to start his or her shift before the sales clerk on duty can go home (finish the shift).

Let’s look at the remaining two dependency types: start-to-start and finish-to-finish.

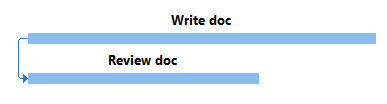

Suppose one person is scheduled to spend 10 days writing software documentation and another one is scheduled to work 10 days reviewing the documentation to make sure it’s accurate and clear. At first glance, you might think start-to-start and finish-to-finish dependencies work equally well. When the writing starts, the review could start almost immediately. Or, when the writing is complete, the review could finish soon after.

But start-to-start dependencies can cause trouble if activities don’t occur as scheduled. Suppose the writer runs into issues with the software and the writing task is going to take 15 days instead of 10. As you can see in the figure, the writing and review started at the same time, which means that the review is scheduled to finish 5 days before the writing. Some of the writing wouldn’t get reviewed unless you caught this error in your schedule logic.

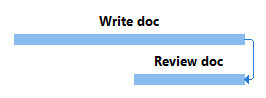

The writing and review activities should be linked with a finish-to-finish dependency. That way, the schedule logic guarantees that the review doesn’t finish until the writing is complete, even if the writing takes longer. This dependency also works if the review takes less time than writing—say, 5 days. With finish-to-finish, you could wait 5 days before starting to review documentation, as shown in the figure below. If the writing takes longer than you expect, the delayed finish date for writing also delays the finish for review.

As you can see, almost all your dependencies will be finish-to-start or finish-to-finish. Another dependency best practice is to avoid negative lag (also called lead), because it implies that you know when the predecessor activity will finish. (You can explore this practice in this movie from my revamped and updated course, Project Management Foundations: Scheduling, which was released in April 2018).